The day after the horrifying Orlando shooting, a friend was inviting me to play Overwatch. It was a weird moment. I felt like, I don’t know—maybe it’s just me, but I really don’t feel like running around with a gun shooting at people right at that moment for some reason.

Some E3 events began that night. Everyone was talking about a new Quake game’s announcement on social media. I found it to be pretty distasteful, and actually felt a little bit bad for the people who had to present this stuff at a time like this. Then again, I always find E3-type events pretty distasteful, so I felt like, well, it’s probably just me again.

But then I saw prominent game designer Jonathan Blow, who I’m pretty sure is not remotely influenced by me or anything I’ve written on the topic over the years, put out this tweet:

The lesson of E3: Game studios are working very hard to build fantasies about how cool it is to be a mass murderer.

— Jonathan Blow (@Jonathan_Blow) June 13, 2016

After the predictable backlash (which is still ongoing at the time of this writing), Jon tried to clarify further:

I’m saying, if you enjoy fantasizing about stabbing people in the neck, that is kind of gross.

— Jonathan Blow (@Jonathan_Blow) June 13, 2016

Maybe I wasn’t crazy. Maybe there really was something actually distasteful about all this. Soon after, I read stories from NPR, The Verge, The Daily Beast, and others, all at least asking good questions. That gave me a bit of hope—are people going to start talking about this issue now?

Social Progress in Media

I identify as both a feminist and a social progressive, and I’m proud of the progress that these groups have made over the past decade both in media and in real life. In most ways, I feel like we’re winning the culture war. Mostly because we’re right, but also because of the persistent efforts of people who cared enough to point stuff out.

Particularly, on the topic of noticing sexist portrayals of women in games and other media, there has been a strong movement to convince consumers and creators alike of our positions. Feminism/social progressive blogs and channels started going viral (most notably among them the YouTube channel Feminist Frequency), and developers have started to actually take notice. As bad as things are now, I think they’d likely be even worse if it weren’t for the strong social pressure against portraying every single female character as a sex object. And even when companies screw up, there’s a consistent and reliable backlash, which to me suggests that it’s only a matter of time before we start to see more real change on this issue.

We’ve gotten pretty good at detecting sexist portrayals of women. We understand that the way women are presented in media really matters. We get that it doesn’t have to “turn everyone who views it into rapists” or something similar for it to be a problem. We know that the effects of media on people are subtler, more long-term and harder to isolate. Like racism, it often does its best to conceal itself, but we’re getting better and better at finding it anyway.

And yet at the same time, it seems to me that we’re a little bit blind to the equally damaging and similarly manifesting problem of glorification of violence in media. I see vocal feminists calling out the sexism of a character design or even a story event, and then turn around and completely embrace some utterly disgusting piece of violence glorification.

What’s the connection between this issue and feminism, you might ask? Violence glorification isn’t strictly a feminist topic. But I would argue that women suffer most as a result of our culture of violence, and dehumanization involved in sexist portrayals is highly related to the dehumanization of violence. Ultimately, I feel that feminists would and should be sensitive to issues of dehumanization generally since they have faced it for so long.

So where is the sensitivity to these messages? Why doesn’t the message these works are sending matter anymore? A lot of videogames, action movies and comic books, if you are looking with the same kind of analytical lens you were using to identify the sexist messages, are clearly sending the message: “violence is extremely cool.” This message is an incorrect and socially damaging one, at least equally as incorrect and as socially damaging as the message that “women are sex objects”.

And yet people don’t seem to notice, or care. Instead, we offer weak rationalizations (such as, “you’ve got to get your violence out somehow!”) or quickly jump to point out that studies have not been able to demonstrate that “videogames cause real world violence” or some such thing. Meanwhile, we would never accept something like that as an adequate response to our complaints about the representation of women in games. It’s never been that we “can show some direct link between A and B”. It’s that these works subtly contribute to an institutionalized culture of sexism—or in the case of violence glorification — of a culture of glorified violence.

So why, oh why, do we have this strange blind spot?

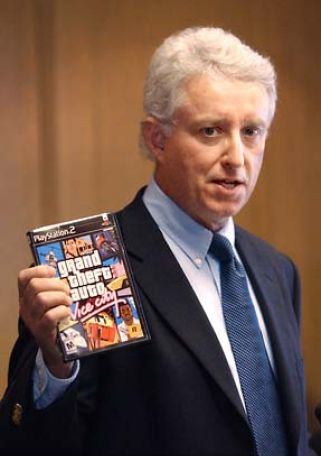

The well has been poisoned

Over the last few years I’ve talked to people of all kinds about the issue. Pretty much across the board, with a few exceptions, I detect some degree of discomfort or disinterest with the topic, if not outright rejection of it, certainly among normal gamer types (especially males), but also even among strong feminists. I believe a large part of the explanation is that the well has been poisoned over and over again by censorship advocates like Jack Thompson and Joe Lieberman back in the ’90s. It is highly unfortunate that this crowd is the one that has seriously taken up looking at the issue of violence in games. Here are the major mistakes that they made in their approach:

- They tried to use the law to legally censor materials, rather than trying to change public opinion. I do not want to legally censor any materials; I want to convince the public that they should not want such materials.

- They considered all violent material equal; they failed to see the critical difference between “violence that is glorified” and “violence that is not glorified”.

- They tried to make the case that “viewing violent materials causes you to become physically violent”, a position which is very hard to demonstrate. My position is that it has more subtle, second-order effects such an increase in a willingness to vote for war, support for harsh criminal justice and general decrease in compassion.

- They seemed to try and make the case that only children are affected by media, when in fact, we all are.

I think their awful and heavily publicized attempts to take action on this topic has made it feel somewhat gross to even go near it for people like myself, who otherwise have nothing in common with a Jack Thompson type of person.

Beyond that, though, even if they had done a good job of making the right points, I think it would have fallen on deaf ears in the 1990s and 2000s. Videogames were just way too cool to be criticized at the time. No one wanted to hear that there was a problem with them. I think things have only recently cooled off enough so that people can take a deep breath and ask, “ok, now what exactly is it I’m looking at, here?”

Anyway, there is a residual resistance to even considering that there might be anything wrong with violence in games because of the actions of these types of people. We have a generation of people who felt like they “already fought that battle” and won. So to hear someone bring it up now brings back all those old feelings.

OK, but not this

The other reason I think there’s some resistance on this point is a phenomenon I’ve been calling “OK, but not this.” Basically, when people come along on social justice issue X, many of them will have an automatic resistance to social justice issue X+1. The example that comes quickest to mind for me is Bill Maher, who generally I think wants to be a social progressive, but has trouble keeping up with the times (to put it nicely). He learned in the last five years or so that gay jokes—jokes wherein the premise of the joke is that a person is gay—are probably in bad taste. There really isn’t any actual comedy there, and it’s instead coming from a vaguely if not overtly homophobic place.

But I also detect that he has some degree of “OK, but not this” when the next issue is making jokes about transgender people, which he still routinely does. He peppers his dialogue with mentions of how the world has gotten “too politically correct” which serves as his signal to say “hey, I got on board with the not-trashing-gay-people thing, just let me have trashing transgender people!”

The Maher example is an almost cartoonish example of this problem, which makes it a good illustration of the issue, although in most people I think this effect is much more subtle. I’ve met many people who were kind of on the fence with the whole “giving a shit about how women are portrayed in games” issue. They eventually came down on the right side, but when you start questioning “well, maybe we shouldn’t be glorifying war in these games, either”, there is a panicked sense of “now wait just a second” or “now you’re going too far!”

I think this “OK, but not this” factor also plays a little bit into the “anti-PC” movement and possibly fuels some of Donald Trump’s success. Many Trump supporters are people who feel “burned” by having to go further and further down what may seem like an endless rabbit hole of behaviors that they have to alter in order to be “politically correct”. They are correct: that list is endless, because it is a reflection of our ever-maturing moral landscape. They are incorrect in getting fed up with the process and giving up.

Attachment

The other big reason we’re blind to this stuff is that we’re just really attached, and we get really defensive. It’s kind of a weird miracle that a movement formed being critical of games on the sexism front, but even there, I notice that there’s this constant need to re-assure people. In an IGN article profiling Feminist Frequency, Anita Sarkeesian echoes something that she says all the time in her work:

According to her, one of the most difficult aspects of criticism for people to understand is the notion of being able to enjoy something while also taking issue with some of its portrayals and approaches to representation.

“A critic does not mean tearing things apart,” she explains. “A critic means saying it is mostly good or mostly bad or some combination thereof. And I think people struggle with this idea.”

“It’s just a matter of being able to hold a multiple, nuanced position,” she says. “It’s [similar to] the way we have relationships with other human beings. It’s not like your friends or your partner don’t [anger you] sometimes, but you still care about them.”

The message is clear: just because we’re criticizing this thing doesn’t mean we don’t still like it, or that you shouldn’t still like it. On its face, that seems maybe like a reasonable thing to say. But why are we sort of “guaranteeing” the “liked” status of videogames? Would it be the end of the world if we originally liked Metal Gear Solid V, but then heard criticism of it, and then didn’t like it anymore afterwards? Is that really any more of a “problem” than you disliking any of the millions of pieces of media you already currently dislike? And even if so, are we really embracing a “just don’t think about the bad qualities” philosophy, here?

How about “listen to my criticism, consider it, and let the chips fall where they may.” Maybe it results in you liking the thing more, less, the same but different in a nuanced way, or maybe it has no influence at all!

It seems that the videogame world is so insecure in our tastes that we’ve managed to convince our most critical voices to pepper their criticism with constant reassurances. We’ve somehow managed to open up to criticism on some issues, so I think we can also open up on violence glorification.

Conclusion

This has been largely an article about our blindness to violence glorification. If you require more convincing that violence glorification in media is a problem—which I know many do—I’ve written a number of articles making that case.

While I criticized the “don’t worry, you can still like these things” approach of Feminist Frequency, I understand why they do that, and doing that is probably a big reason why they were able to slip through the “impenetrable videogame defense matrix”. I should also mention that FemFreq is actually pretty good when it comes to pointing out violence glorification in games. They often tweet about the violence in games, and they made several mentions of the violence in their Uncharted and Tomb Raider reviews.

But I don’t think they go far enough, and I’m not sure the rest of the feminist / social progressive world is on the same page with them on this issue yet. While I’m happy to have seen the reaction to this year’s E3, I’m not exactly convinced that people are going to stick with it. I follow a lot of prominent feminists and social progressives on Twitter, and I almost never hear anyone talking about this issue. Instead I actually hear a lot of them issuing blanket praise for some of the worst offenders in violence glorification, like Fallout 4 with its “kill porn” slow-motion VATS snuff-camera.

It’s time we started really looking at this stuff and asking “what message does this send”? Don’t make excuses for it, even if you like other things about these things. Sure, the violence in the story may be justified (i.e. out of self defense), but the storyteller set things up in such a way so that violence would be justified. That’s the reason we create puppy-kicking villains. Not only justified, but so justified that we can even have fun with it. Why? Of all the stories you could have told, why did you tell that one?

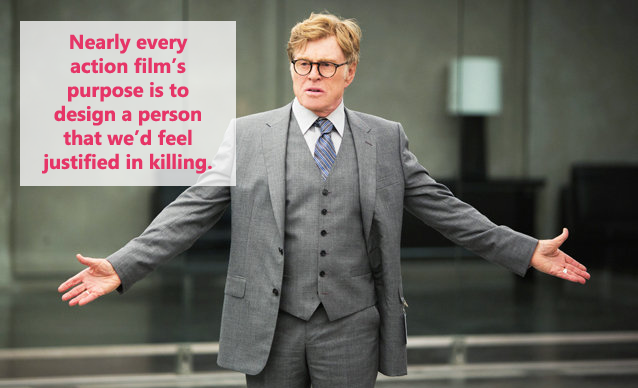

I watched Captain America: Winter Soldier with some friends recently. There’s a scene where the Bad Guy shoots his housekeeper dead because she witnessed the Dark Ninja (I refuse to get his name right). Bad Guy brutally shoots her dead, and a sound of “general distaste/objection” came out of my friends, because, indeed, it was pretty distasteful. But I said, in “defense” of the movie, “yeah but he needs to do that, so that we can do what we’re gonna do to him later!” I hadn’t seen the movie before, but you don’t need to have seen it to know that nearly every action film’s purpose is to design a person that we’d feel justified in killing; a contrived scenario wherein it’s easy to believe that violence is the answer.

The fact is that in many ways, we live in a culture of violence, especially in the United States. We’re obsessed with guns, we vote for wars of aggression, we have a shockingly inhumane criminal justice system. We even use violent language for everyday events, like when Jon Stewart “eviscerates” his next commentary target or when you’re “gonna kill” your friend for not returning the book you lent them.

Art is a tool that we can use to communicate values to each other. Those values can be, and often are, positive, morally correct things that make the world a better place. They can also be negative and perpetuate bad ideas. That’s why we’re so tuned into the sexism stuff—we know that when media sends the signal that girls can’t do this or that, that that has a real effect on society. The answer is not going to come down from on high in the form of censorship or regulations, and I don’t think it should. It’s going to come from people who care about the messages we’re sending with media.

Right now, AAA videogames, action movies, comic books and TV shows are actively working against the non-violent values we know to be correct. Only when we wake up to this fact will this stop, and hopefully we can start using these media to reverse course.

If you’d like to support my work, please visit patreon.com/keithburgun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.