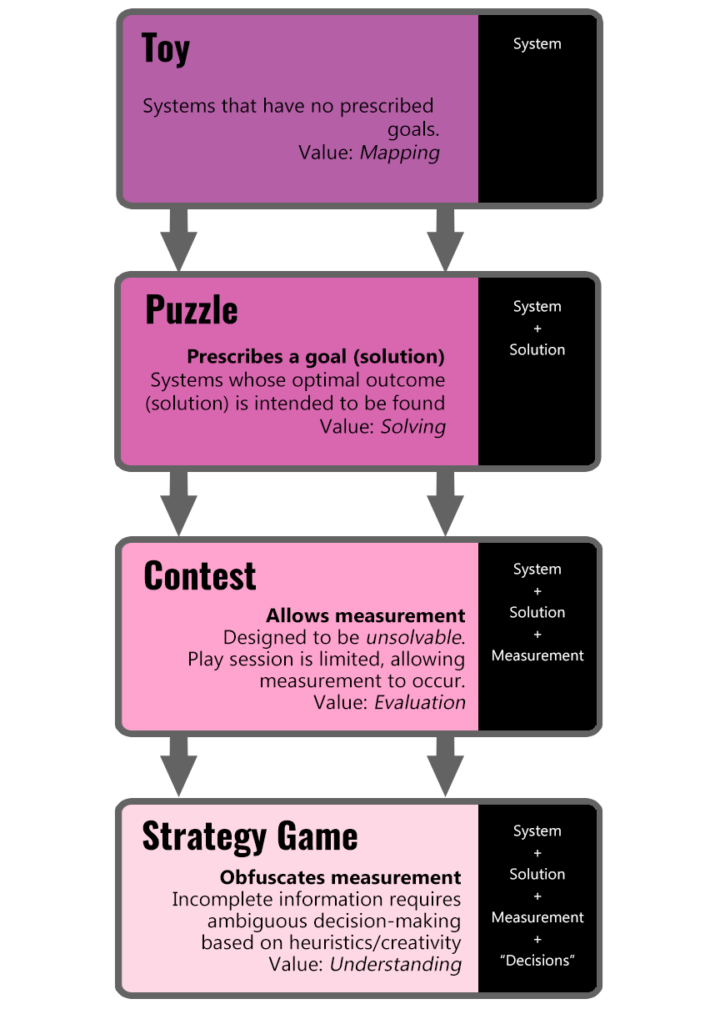

Within “interactive entertainment”, we can divide things into four forms – patterns of design that, in theory, work in a certain way. By understanding these forms can we develop guidelines for better interactive system design within those forms. Please note that the words used here are new, prescriptive definitions for words, designed for use by specialists, and not intended to override/remove other usages.

Notes on the VALUES

The words I’m using for “values” are also prescriptive in their definitions, if only slightly.

The value of a TOY is Mapping, or Exploration, or even possibly “play”. The toy’s value is in learning all of the ins and outs of an interactive system. Playing with a toy is actually piecing together its ruleset, finding its edges and its possible interactions.

The value of a PUZZLE is Solving. The colloquial definition is puzzle matches somewhat well – think of a Sudoku puzzle, or a riddle. We’re scouring the edges of the ruleset (which we have to already have in order to engage with the puzzle and attempt to find the answer) attempting to find the solution.

The value of a CONTEST is Evaluation. This, like the Puzzle, is also very similar to what we’d expect based on colloquial definitions. Who has more of Resource X? It may be speed, strength, memorized facts, or even luck (Roulette, for instance, is a luck-contest).

The value of a GAME is Understanding. This is the one that requires the most explanation, since I’m using the word “understanding” in a prescriptive way too (it’s the closest word I know for the phenomenon). Understanding is the act of adding to a complex web of heuristics that a player will build over time which the player uses to inform decisions. “Fun” in strategy games comes from those moments of building this understanding.

The way that understanding happens is that an ambiguous decision is entered into a system, and then feedback is presented to the player. In order for this feedback to result in understanding, the decision must be endogenously meaningful and the consequences have to be permanent. From this, the player can learn to “understand” a specific interaction.

How It Works

While each new system carries the properties of the system(s) before it – i.e., a contest has the properties of a puzzle and of a bare interactive system – each new form functions in a different way and has different values. A game is a subset of contest, which means it is indeed measuring something, but the most important element becomes the newly added element. In the case of games, that would be decision-making.

The most important difference is that each form has different, and indeed conflicting values. So, the values of a game conflict with the values of a contest, because a contest is a measurement, and decision-making shouldn’t be possible, as it would distort the measurement.

Further, if you’re engaging in a game that has a major measurement component to it – for example, Sumo wrestling, then your decision-making may be completely overridden by this.

Since each form has conflicting values, we can use this system to identify and reduce or remove internal conflicts, thereby resulting in a more pure and effective machine at producing one of these values.

More information:

My book, “Game Design Theory: A New Philosophy For Understanding Games”

You must be logged in to post a comment.