It is common to hear players talk about “tactics” and “strategy” in games. In this case, the colloquial understanding of these terms happens to be pretty useful, in that it maps well to something that actually goes on in playing strategy games. With that said, it’s worth taking a moment to clarify these terms:

“Tactics” usually refers to “short-term decision-making”. Questions like “should I move this character two steps forward, or three steps forward” are questions of tactics. Tactics are micro-level decisions in strategy game play.

“Strategy” usually refers to “longer-term decision-making”. Questions like “should I be aggressive early, or be defensive now and attack later on” are longer-scale choices about a game that players make. Strategies are macro-level decisions in strategy game play.

In both cases, we are talking about a grouping of gamestate information over time and how it changes. I refer to this grouping as an “arc”.

A specific example of an arc: in a Rogue-like, a monster comes on screen. We can call my encounter with that monster a short “arc”. We can also call me going from level 5 to level 6 a longer arc. A shorter arc might be an individual exchange of damage between myself and the monster.

There is no hard line dividing tactics from strategy—it is a continuum with many being grey areas in between. There is room for debate about whether a given interaction in a game is more strategic, more tactical, or perhaps squarely in between.

With that said, it’s still a useful tool for designers that can help them create more elegant, deep, and perhaps most of all, time-efficient games. Arcs are one of the fundamental pillars of form, or structure in strategy games, and so they should be considered carefully in any design.

How Not to Use Arcs

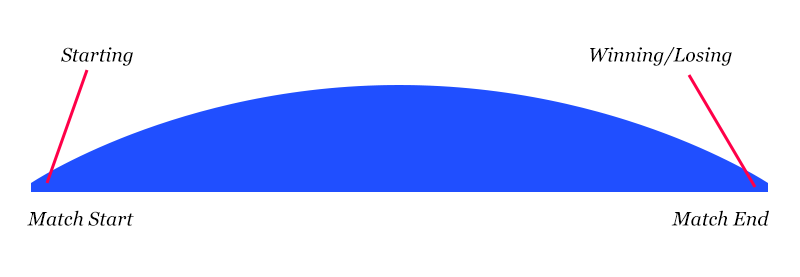

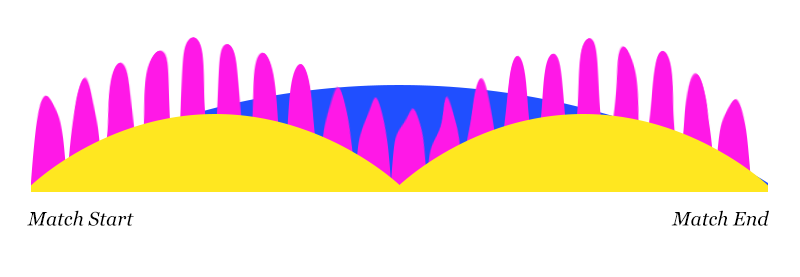

A good use of arcs is a balanced, stable use of arcs. In order to explain what that means, let’s take a look at a visual representation of arcs in a single match of a given strategy game.

Above, we see a single arc of a game. This is the longest arc – the arc of the match itself. The player goes from starting the match, to eventually finishing the match, resulting in a win or a loss.

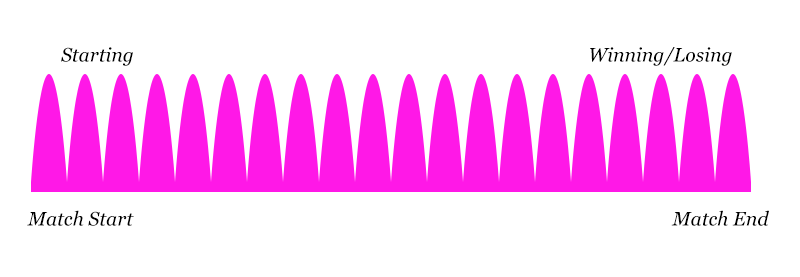

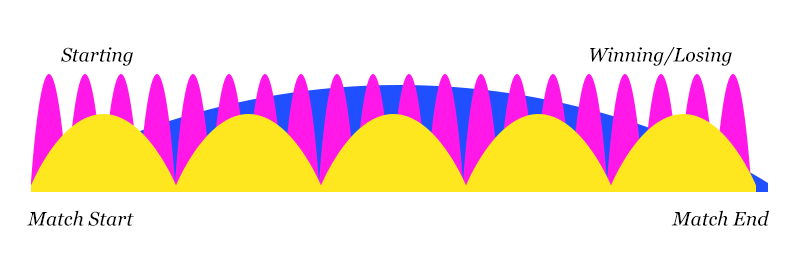

Of course, there are many other things going on in a strategy game. Let’s take a look at what many small arcs might look like on the same spectrum.

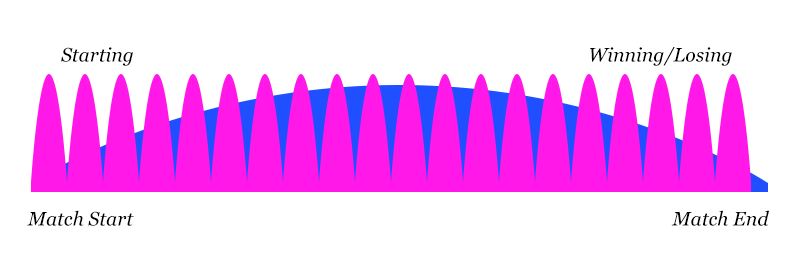

In this example, we have a repeating pattern of short arcs which resolve quickly. Many popular strategy games take a structure like this, but then simply “add on” the blue longest arc (winning and losing), and we get something like this:

In this example, we have a repeating pattern of short arcs which resolve quickly. Many popular strategy games take a structure like this, but then simply “add on” the blue longest arc (winning and losing), and we get something like this:

This is certainly the case for something like Street Fighter or other fighting games, where you have a small arc of attacking each other that happens until the health bar of one player runs out. The kind of decisions being made in a system like this are extremely tactical and short-term-focused, which is why the purple arcs are very short.

To make my point even more clear, imagine a version of Street Fighter which simply tallied all damage dealt by both players, and after 60 seconds, the player who had tallied more damage wins. In this example, it is very clear that there is a basically endless, formless, repeating pattern of a-punchin’ and a-kickin’ that is arbitrarily cut off at some point. In my example, it was 60 seconds, but we can easily imagine a 10 second version or a 400 second version, without damaging the gameplay much. Popular sports like basketball and soccer are also extreme examples of this problem.

Why Bad Use of Arcs is a Real Problem

This is something I’ve touched on before, but many popular strategy games have this problem and other related problems. They have some short gameplay loop that just “shuts off” at some point, usually because a timer, health bar, or victory points total filled up or emptied out. This point is often somewhat arbitrary, which leaves the ending feeling (and perhaps being) meaningless.

After you “complete” a match of Civilization, you are given a victory/defeat screen, and then you are given two choices: “return to main menu”, and “just one more turn…”. The latter choice lets you continue playing even after you have won or lost. In a more-structured system, it would be clear how this is a totally absurd prospect. Want to keep playing Chess after I captured your king? The more tightly “playing” is tied to the final outcome, the more clear it is that there can be no “playing” without the possibility of winning.

Arcs is one of the main ways you achieve a structural through-line between playing—making strategic and tactical inputs—and winning or losing.

The second problem with bad use of arcs is a more practical one: games that look like the above chart tend to get boring more quickly because you’re doing the same thing, quite literally, over and over again. And whether or not you consciously acknowledge the arbitrary length issue, your brain is aware of it. It is apparent to your subconscious that you are doing the same thing over and over and over again. To the extent that you embrace structure via good arcs, this is less and less the case.

Good Use of Arcs

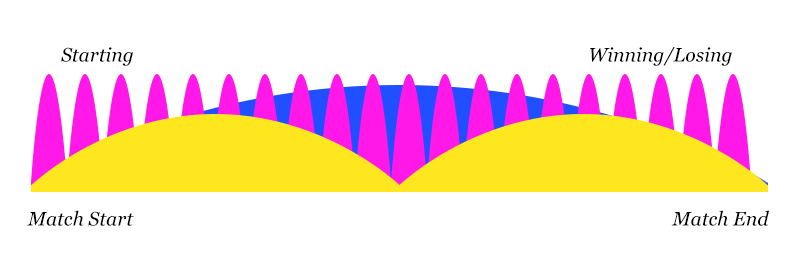

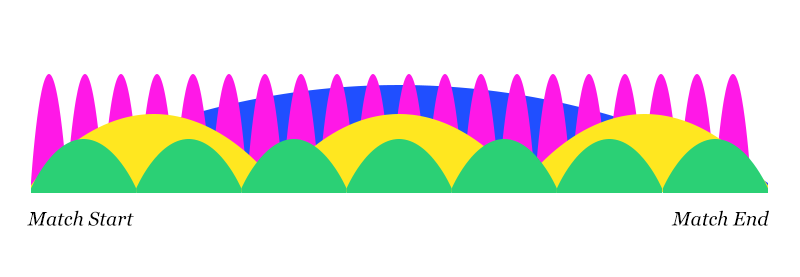

So far, we’ve talked about the longest possible arc (match-completion, in blue), and the shortest possible arc (tiny tactical decisions). In order to avoid the problems above, let’s add an arc of medium length.

Above, we’ve added a yellow arc to the game. Already, what we have done here is make it so that all of those little purple tactical arcs mean something slightly different, because they are now taking place in a different spot on the yellow arc. Here is a very rough visual representation to demonstrate that point:

Above, we’ve added a yellow arc to the game. Already, what we have done here is make it so that all of those little purple tactical arcs mean something slightly different, because they are now taking place in a different spot on the yellow arc. Here is a very rough visual representation to demonstrate that point:

(Side note: this is sort of related to the ideas behind frequency modulation and additive synthesis, which work similarly.)

It’s true that the blue arc was also doing this for them even before we added the yellow arc. It does mean something that we are halfway through the match or near the end, or near the beginning. However, this is a weak arc relationship.

Arc relationships can be considered “weak” when they are too drastically different from each other in length. At some differential, it becomes too difficult for the player to understand what this tiny tactical decision means for the larger arc.

No one has trouble establishing the blue or the pink arcs in strategy games. This article is all about the yellow arcs, and how to do them correctly. When talking about yellow arcs, it is best to think of them and their “parent/child relationships”. We should be primarily concerned with the arc’s length as compared to the length of its parent and its child.

In the case above, it is the case that the yellow arcs are too large compared to their “child arc” (the purple arcs). Let’s imagine those arcs a bit smaller.

At this rate, there are about four of the pink arcs per each yellow arc. You can imagine that having arcs of this size are probably quite easy for a player to grasp as their closest “parent arc” while working on the purple tactical arcs.

When designing, you may want to re-distribute the arcs several times throughout the process to get as “even a distribution of arc length” as you can. Here is an example with a fourth arc length thrown in there that might make sense.

Arcs in Practice

This might all sound very theoretical, and it is. But I am also in the process of adding long arcs to Dinofarm Games‘ Auro.

I’m very proud of the game Auro is, but one major problem it has is a near-total lack of long arcs. It is an extremely and purely tactical game. This has all of the problems I talked about above: it has an arbitrary length, the ending feels arbitrary and is of questionable feedback value for that reason, and it can feel repetitive.

I’m very proud of the game Auro is, but one major problem it has is a near-total lack of long arcs. It is an extremely and purely tactical game. This has all of the problems I talked about above: it has an arbitrary length, the ending feels arbitrary and is of questionable feedback value for that reason, and it can feel repetitive.

As I recently announced on the Dinofarm website, we are launching a new spiritual successor to Auro, tentatively titled “Alakaram“. We have many changes planned, but design wise, the biggest change that I am working on is how to add long arcs to that game.

Easy approaches would be to add stuff like experience points, levels, items and equipment to the game, as many popular games do. These would, in fact, count as longer arcs, but I have other game design issues with such things that are beyond the scope of this article.

For now, I will simply say that Auro is a game fundamentally about moving actors on the grid, and so having some internal spreadsheet inside the Auro character that has no direct connection to the grid is problematic.

My proposal, which we are currently testing out, is to implement the following changes:

- The objective of the game is no longer score based. Instead, you must “capture” six totems spread throughout the map before running out of health.

- You now create hex-circle-areas of “influence zone” with monster kills (instead of getting points) which decay over time. This influence is the way that you capture the totems.

This is an extremely simplified listing of the proposed rules (for more detail on it, read this thread on the Dinofarm Forums), but the point is that I am trying to create longer strategic arcs that utilize the space of the map. I imagine players making medium and long term goals about when they will try to capture this totem versus that totem, when to back off and collect some resources, and so on.

Consider Arcs

I have no idea whether the above idea will actually work, but I am very confident that the principle behind it is correct. If the idea does not work in testing, I will try other things.

In my experience, this way of thinking about strategy game design is not common among designers. I believe that thinking of arcs in this way will greatly benefit us all. With it, we can create more efficient games that are actually no longer than they have to be. If you have a good structural understanding of your arrangement of arcs, it suddenly becomes quite easy to know how short or long your game should be, which historically has been a pure mystery.

Not only that, but smart use of arcs means that each part of a game feels more unique and special, because it in fact is. And it achieves this without having either a chaotic, random set of game-states that are barely connected to each other. I believe that games designed with this philosophy will also feel less in need of “content”. I would attribute much of the belief in “mass-content design” to the fact that our systems are structurally unsound, and therefore exhausting to interact with, to begin with.

Enjoyed this article? Consider becoming my patron on Patreon.com!

You must be logged in to post a comment.