When I was 11, my family got its first computer: an AST “Advantage!”, which sported a 66 MHz 486 processor, 4 MB ram and 32 MB of hard drive space. It wasn’t the greatest computer, even for the time, but it did have QBasic on it, and having always wanted to make games, I immediately dove into coding.

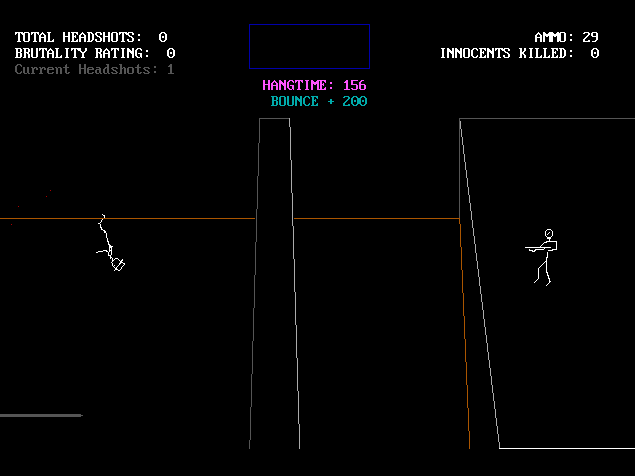

I stuck with QBasic for the following decade or so simply because I was comfortable with it. I made a bunch of shooters, platformers, and actually a lot of weird games. I made one called “Kill the Innocent” (download it here, but you’ll need DosBox to make it work), which featured stick figures walking along a bridge, and you aim a gun at them and just kill them. I remember coding a detailed system for how the man’s top-hat would float gently to the ground, and a very simple physics system that would allow you to juggle the man’s head in mid-air with shotgun blasts. (I guess I was subtly picking up on the ugliness of violence in videogames even back then, although I certainly wasn’t conscious of it, being that my AST Advantage was running Doom so often.)

The thing was, though, that in all that time, I really wasn’t learning much about programming. I was kinda just re-using the same ten or so programming keywords – everything was hard-coded, nothing was remotely “modular”. In other words, I wasn’t really learning to program. I had no idea how to “import a spritesheet” or build something that would run on Windows, let alone an iPhone. I just wasn’t a programmer, really.

My difficulties learning to code

I tried over, and over, and over again in my teens and twenties to branch out and learn to code in something a bit more modern. I can’t tell you how many “Learn [Insert Language Here]” books I bought, got through the first three chapters of, and then gave up.

The short answer to why I gave up? Basically, it just seemed really hard for me. More specifically, it was a kind of hard that’s particularly difficult for me to apply effort towards. I now understand that programming takes a very particular kind of perseverance, and an almost faith-like belief that “I can and will find the answer”.

It’s possible that part of the reason was that I was an “art person”. I wasn’t into math or science in school, but I excelled in music, visual arts, and writing. I think I sort of identified myself as a “creative type”, and so when some compile error reared its head, and wouldn’t go away after the first two, three, four, five times I tried to fix it, it was easy to feel like “well, I’m not a programmer, after all – I’ll need a programmer to fix this.”

Ultimately, like anything else, you just have to believe that you can do it, and you will do it. But believing that isn’t trivial.

The Non-Programming Designer

For the first decade or so of my career as a professional game developer, I’ve taken a significant or leading role in the following disciplines: visual art, music composition, sound production, graphic design, web design, writing, game design, marketing, and probably a handful of other skills. Basically: literally every single thing required to make a moderately high production value game *EXCEPT* programming, I did.

My thinking was, well, if I’m doing all of that other stuff, it’s reasonable to get help from another person to take the programming role, right? That was always my opinion. I actually even kinda resented the idea that not only do I have to be the guy to do the other dozen things for a game, but I also have to program it? I should be able to find someone to fill in that gap.

And actually, I’d argue that that is reasonable, and it’s doable. I’ve gotten several games out the door doing exactly that. To be clear: you can operate as a non-programming designer. I found teams or individuals who were looking for game designers, artists, composers, and filled those roles.

My argument is that while you can do this, to the extent that you’re a game designer, you shouldn’t.

Game designers – real game designers, anyway, are people who are actually experimenting with systems and trying to do something with rulesets. Technically, someone who designs a generic puzzle platformer or tower defense game is, of course, a game designer, but I’m not talking about those people. If you’re “designing” a Flappy Bird clone, it’s probably fine if you’re not the person programming it.

For people like myself who are experimenting with new systems of interactivity, the “get a programmer” plan just really isn’t practical, because unlike a Flappy Bird clone, serious game design is hard to get right the first time. Or the tenth. Or the hundredth. You need the flexibility to implement an idea when it comes to you at two in the morning like a lightning bolt. Writing an email or a to-do for someone else who might not get to it for a day or two is just too slow.

You need to be personally in the loop of playtesting, iterating and re-iterating yourself. Tweaking variables, changing how things are arranged – you need to be in there doing that. Otherwise, you have a “play by email” sort of problem where even small things can take a long time to do.

Keep in mind that there is some finite amount of time that you will end up working on your game, so you want to use it as best as you can. As the designer, being the – or a – programmer on the project, you can massively increase the number of “iteration loops” that fit into the development timeline (no matter how long or short that timeline is!)

Finally, I find that I have to balance “making the right design calls” with “making a person feel like I maybe don’t respect their time” when working with a programmer. Most of the time, if I ask a programmer to code something, later on we’re gonna find out that that thing I asked him to do is going to get thrown in the garbage. It’s one thing to warn people up front that this will be the case, but it’s another thing to be in the moment, telling a person “yeah, about that thing I made you code last week… we’re ditching it”. I don’t want to be in a position where I might be even a little bit inclined to hesitate to make the right call just because it could piss someone off.

What About Board Games?

Board games are a good place to learn game design, and some designers, depending on their philosophy and goals, may be able to just operate making board games for their whole careers. Here’s the thing though: despite the fact that there are way more well-designed board games than there are well-designed videogames, board games, as a medium, have some problems. Lots of people believe that for bad reasons, like they hate that they’re turn based, or they hate that they have to learn rules, or maybe they just hate that board games don’t have Rapid CGI-Beheading Quicktime DLC. Those are not the real reasons. Here are the real reasons that board games are problematic:

Board games are a good place to learn game design, and some designers, depending on their philosophy and goals, may be able to just operate making board games for their whole careers. Here’s the thing though: despite the fact that there are way more well-designed board games than there are well-designed videogames, board games, as a medium, have some problems. Lots of people believe that for bad reasons, like they hate that they’re turn based, or they hate that they have to learn rules, or maybe they just hate that board games don’t have Rapid CGI-Beheading Quicktime DLC. Those are not the real reasons. Here are the real reasons that board games are problematic:

- Working with physical components causes some problems. It’s difficult to have much precision in setting a good information horizon.

- Lower “practical information density” – based on the practical limitations of what we could reasonably expect players to fiddle with in terms of rule upkeep, the information density – information per game element – must be oppressively low. For more detail on this and the above point, listen to this episode of my Clockwork Game Design podcast.

- Rapid feedback. Make a thing, slam it up on the web, and get feedback from lots of people, strangers even, within hours. Meanwhile getting feedback on a boardgame requires scheduling and a lot of other real-life annoyances.

- Commercially not really viable – I assume a lot of designers would like to make a career out of their craft, and, some exceptions aside, it’s much harder to do that with paper and cardboard than it is with computer applications.

Ultimately, as I said, I do think board games are a great place for designers to learn a lot about the craft, and I do think it’s possible to make some very good games out of just about anything. I just think it’s a lot harder to make a great board game than it is to make a great videogame, and I think that making a great videogame is already near-impossibly hard.

Becoming a Programmer

The development of Auro: A Monster-Bumping Adventure took us five years (and counting). A big reason for that was, it was an original strategy game and I wanted to get it right. We could have launched a sorta generic, boring Rogue-like back in 2011 if I didn’t care about creating something special. So we iterated, and iterated, and iterated.

But eventually, our first programmer had to move onto other things, and so we got another. And another, and another. Eventually, by about late 2013, we had run out of a lot of programmer-steam, and there were times when Auro kind of seemed like it was dead in the water. So being in that position, I sort of just had no choice – I had to learn to program now, or else all this work would have been for nothing.

Being in that position – and also, maybe, just being a bit older and having more of an attention span – helped me to really dive in and get comfortable with the codebase. Ultimately, I ended up coding a huge chunk of Auro‘s final code!

More recently, I’ve been taking an online Unity course through Udemy, as well as reading a few books on programming patterns and things like that. Obviously, I still have a long way to go, but I have gotten to the point where I can at least prototype stuff and iterate on my own, and it’s extremely freeing for me as a game designer.

I still do think in an ideal world, a designer would have a “lead programmer” who specializes in that, and can set things up in a way that’s not horrible, and help maintain some semblance of order in a codebase – especially for a larger, more complex game.

But what I do know is that game designers like myself, who care about producing new, interesting, deep systems of interactivity, just really need to learn to code. You can’t be relying on others, and you can’t really be relying on paper and cardboard. Do what it takes – pay a tutor, take a class, or just lock yourself in a hotel room with a book. I’m absolutely not saying you need to become a John Carmack and learn to build new engines with assembly language or anything like that – you just need to be able to use stuff like Game Maker or Unity to get a game from idea to prototype.

If you’re a “creative type”, videogames need you!

—

Version 1.0 created Nov 11 2015

If you enjoyed this article, please support my work at Patreon.com!

You must be logged in to post a comment.