One of the things that’s scary about being a writer is that the things you write keep existing, unchanged, the way that you wrote them, back when you wrote them. Sometimes it’s difficult to go back to a piece you wrote even six months ago and re-read your own work. There’s just always so much stuff that should be fleshed out more, or that should be re-arranged, and so on. You read your own work feeling the embarrassment of knowing that others are reading this, too.

Going back years is even worse. I had an old blog that started in 2007, but the years of 2010-2012 or so was when my writing career really started, largely working for Gamasutra, but also other sites like Destructoid and, of course, my own blog. 2012 is also when I wrote my first book, Game Design Theory: A New Philosophy for Understanding Games. Looking back at a whole book you wrote years ago is a mortifying experience. I try to do it occasionally, because I think there’s a lot that I can learn about myself, my history and my path forward from looking closely at my old work. And often, it’s not nearly as bad as I fear it will be (I still think that, with additional contextualization that the book does not provide, most of what I wrote in my first book is true).

I found this old (2012) article about theme in games which I had written and then several years ago taken down so that I could update it. It was called “The Importance of Theme”. I thought it’d be interesting to take it bit by bit and do a 2019 response, creating a sort of dialectic over time that may be useful, or at least entertaining for others to read. Here goes!

Reading note: the original text is in italics.

“Theme” is the word I use to refer to the metaphorical names, images and concepts that game designers apply to their games.

Response: I don’t like the phrase “apply to their games”. The implicit idea here is that players can look at a ruleset in a sort of blank, context-less vacuum, like how a computer performs calculations. Humans can’t and don’t do that probably ever, but they certainly don’t in the typical game, which is often set in a world rich with setting, characters, music, colors, all of which are evoking some comparisons and responses over others. Furthermore, I’d argue we are almost always designing with some kind of theme in mind, possibly except in the cases of extremely simple abstract strategy games.

Why do we do this? The reason most people jump to is “fantasy simulation”: the idea that “I get to be a superhero, saving the kingdom from a dragon!”, or “I get to be Spider-Man!”. While this is definitely a possible reason for adding a theme to a system, and while there may be some benefits to working in this way, it’s generally not a plan that is structurally sound. Don’t worry, I’ll explain what I mean by that.

Response: (I thought people would be worried about that?) I would say that a great many things which work very well as art are not structurally sound. I guess it is more important for strategy games to be structurally sound, but it’s not clear that that’s all I’m talking about, especially with the mention of Spider-Man.

Firstly, it’s good to recognize that not all games have a theme. Abstract strategy games such as Go or Checkers don’t have themes. I’ve heard people try to argue that Go does have a theme, and while I’m sure you can figure out some way to make that statement true, I think that in doing so, you’re stripping away the usefulness of the term. A videogame such as Tetris could also be said to have no theme. Most word games like Scrabble, Boggle or Letterpress also can be said to have no theme.

To say there is no theme to a game is to say that there is no metaphor blanketing the game. In Go, when I place a stone, that action does not “represent” anything thematic. I am not “placing a Samurai warrior”, nor am I blasting a hole in an alien ship’s shields. I am simply placing a stone.

Response: Firstly, I hate when people start things off by saying “firstly”. If it doesn’t represent anything, then why do I care when it happens? Why am I invested at all? I think, sure, it doesn’t represent some visual image or something linguistic, but it does contain a lot of human expression. Maybe it’s kind of aggressive. Maybe it’s really clever or tricky. Maybe it’s surprising. Maybe it was played very quickly and expresses a ton of confidence. There is history to this spot, this shape that is now getting threatened is your oldest shape, maybe it is a shape that you won several battles with earlier, and now it is being threatened. The shapes are like characters, the list of events is a narrative, etc.

I’m sure you can figure out some way to say that Go has no theme, but I think that in doing so, you’re stripping away the usefulness of the term.

With regards to representativeness, that move can certainly “represent” mechanical concepts. In Go, playing a stone close to an opponent’s group might “represent” the player’s challenge to his opponent, for example. This would not fall into the category of theme as I mean it, however. Theme is only referring to non-mechanical information.

Response: Okay, so I tried to head this critique off at the pass. The truth is that on a practical level I mostly do use the word this way. But it feels a little bit weird to care so much about the distinction. Why is theme “only” referring to non-mechanical information? Who says? And even if we agree to this statement, I think it’s hard to draw that line in practice.

Literal, Metaphorical, Thematic, Abstract

Some people use the word “metaphor” where I use the word “theme”. That’s fine, but there’s one weird thing that happens with these words regarding this topic that makes me stick with using “theme”.

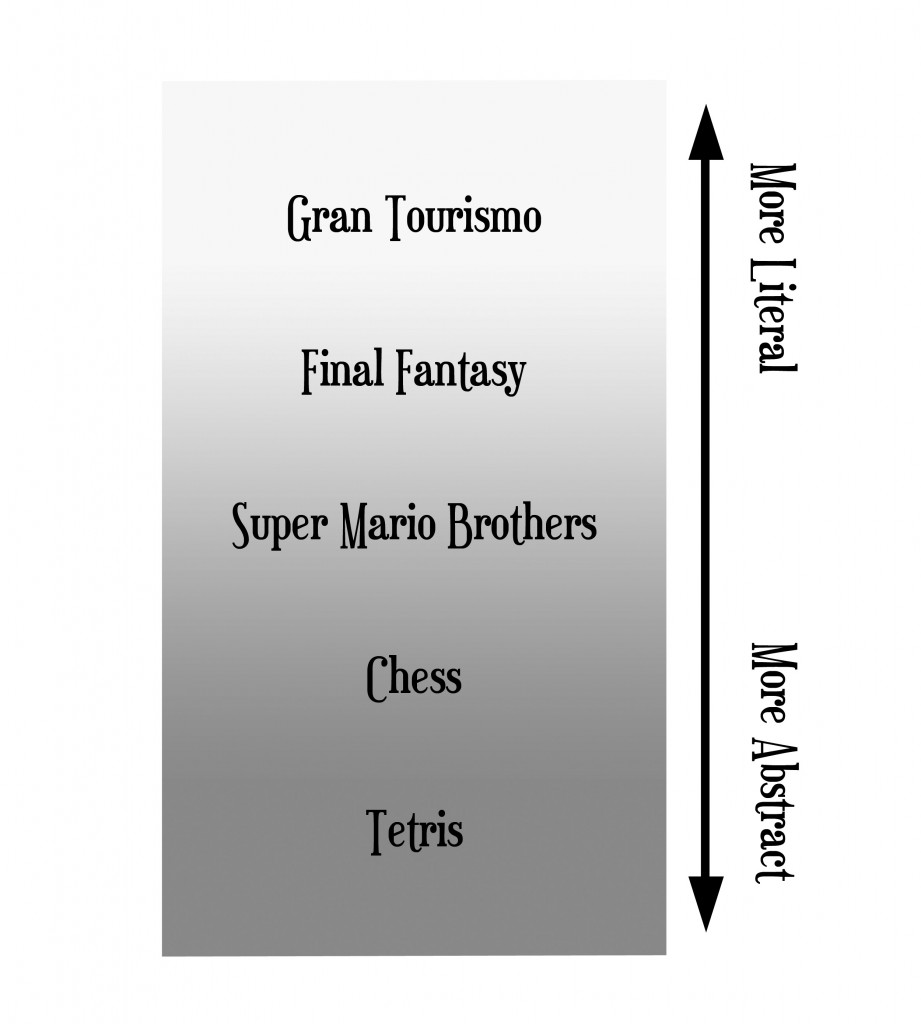

Firstly, here’s a chart that I pulled from my book that shows an example of the continuum as going between “More Literal” and “More Abstract”.

By “literal”, I mean “taking words in their usual or most basic sense without metaphor or allegory” (got that from the dictionary). So, as we travel away from abstraction, we move towards it being strangely more literal and more figurative at the same time.

Tetris is on the bottom, being totally abstract. Just above it is Chess, which has a very slight “war” theme, with pieces being represented by carved images of actual military units (or, at least, symbols that represent them), and a general structure that we can accept represents two fighting armies on a battlefield. Then, Super Mario Bros., which lives in a sort of no-man’s land between abstract and literal. Finally, at the top, we have the simulation type of stuff which is doing its best to be as literal as it can be. In Gran Tourismo, that image of a car represents: a car.

Granted, in reality, it is not a car. A car is something that exists in the physical world and is made of metal and burns gasoline. This image we are seeing does none of that, but it is still doing its best to be as close as it can to being a real car.

So, here’s what’s weird. It almost makes sense to call this “no-man’s land” the “thematic” zone, with the top area being called literal and the bottom being called abstract, like this:

In Super Mario Bros., a mushroom represents a power bonus item. It’s not abstract, per se – there is some thematic/artwork representation going on – but it’s also not literal. The mushroom isn’t trying to be, or evoke the idea of “a real mushroom”. Instead, the creators are using the image of a mushroom to represent something totally different than a mushroom; an icon, if you will. Perhaps you could also use the word “poetic” to refer to this kind of theming.

Response: I really should have read some Saussure or anything about semiotics before writing this article, probably. But this is all fine I guess.

Importance of Theme

Now that we’ve gone into some of the ways in which games can be thematic, we can ask: why do we theme games at all? Or, alternatively, why do some games lack a theme?

The greatest game ever designed isn’t worth anything to people if no one knows how to play. So a big part of our jobs as designers is teaching players how our games work. The most basic way in which this is done is the classic “game manual”, wherein the rules are listed in their totality. While this is certainly something every game should have (as it’s great as a reference), there’s a large number of players who aren’t going to take the time to read a manual for a game that they have no idea whether they’ll like or not. I got the boardgame Power Struggle almost a month ago, and I still haven’t played it. Let me tell you, it’s a Power Struggle getting through the rules to that damn thing.

Response: I eventually played Power Struggle. It was meh.

The classic game manual is simply not the best way to teach people. Most videogame developers realized this in the last decade or two and have since turned to the tutorial as their preferred method. The tutorial is sort of an interactive manual: it’s linear, and quite like the manual, it’s something you have to “get through” before you can begin to play. Because of this, tutorials can be boring and annoying to endure, even if they’re probably a step up from game manuals.

Is there any other way that we can teach people the rules to our games? This is where good theming comes in. Generally, theme works as a kind of shorthand. Human beings already know tons of little bits of information about the world and how various things work. If you give them a mouse-cursor that looks like a hammer, that tells the user a lot. “I’m probably going to be whacking something down with this, or possibly building something”, they’ll likely think, because those are the sorts of things we generally do with a hammer. If you flash a little silhouette of a nail, you can be sure that they’ll feel like they should click on it. You don’t even have to tell them anything: this is basically free information.

Response: I think I am sort of misunderstanding how this “free information” thing works to some extent. Often, the “theme” is tied up in mechanics, and vice versa. It isn’t necessarily free information at all if you theme something as “swordfighting” in your game. It’s free information if you have swordfighting and a health mechanism and other common mechanisms often found in combat games. A lot of where “free information” comes about isn’t in this symbolism way (although some is, I would grant), but rather just in the relationships to other existing popular games.

You’re almost certainly not going to be able to teach someone all of the rules of your game with theming alone, but you might be surprised how much you can teach them. Going back to Super Mario Bros., the Goomba monster was designed to look as though he could be squished.

Theming is also important before a player even gets to playing your game. When they first see some kind of promotional image, they’ll already start putting together some imagined version of what general kind of stuff you might be doing in this game. Our early version of Prince Auro had one really massive problem in this regard: no one knew what the hell this guy did! When we redesigned him, we gave him a magical looking staff, and suddenly everyone who looked at him knew, at least, that this was a game about casting spells. Free information!

Theme can be thought of as a scaffolding, or rails, for the player to hold onto while learning the game.

Bad Theming

So, we can basically get free information into the brains of our users by selecting the right graphic or icon or word or setting for our game. But if we’re not careful, theming can actually work the other way, and be counter-intuitive.

For instance, I’m not so sure that the mushroom is the best icon to represent what a mushroom actually is in Super Mario Bros. – the closest connections I can draw between “getting big and strong” and “mushrooms” would either be an Alice in Wonderland reference, or a reference to psychoactive mushrooms. Further, the mushroom slides around. How does that make any sense? Shouldn’t it be something that looks like it can slide around?

Modern videogames are much more held back though in this regard. Unfortunately, most modern developers do not think along the lines of:

“How can we choose images that help convey how this game works?”

but rather, they seem to think along lines such as:

“What would be thematically consistent, or realistic?”

In other words, modern game developers tend to use theme for theme’s sake. The theme is not subservient to the gameplay, but rather, quite frequently the other way around. The story calls for a battle to take place in an elevator, so now you’re fighting in a small constrained elevator. Is this the best setting to bring out the best gameplay this system has to offer? Probably not, but it’s what the story calls for, so – sorry, gameplay!

This is problematic, because games are all about the playing of them – that’s what makes them games. You can (and many do) completely ignore the thematic elements such as story and music and even much of the artwork in a game, but you can not ignore the gameplay. The gameplay is what you are doing.

Response: who says that that’s what makes games games? Yes, you are “doing” the “gameplay”, but where exactly does the gameplay end and the other aesthetic or narrative qualities begin?

Further, even if you strive to, as a player, “focus on the thematic elements”, the problem is that this tends to wear off the moment you’re presented with a problem that needs solving. During problem-solving, the brain can not afford to continue processing information that’s irrelevant to the problem at hand. It no longer matters that you’re “in an elevator at the Evil Corporation Hotel and your name is Trevor Porter of the NYPD and you’re in love with your sidekick but don’t know how to tell her”. That information is completely gone from your brain the moment that you have to calculate the trajectory you’d have to jump at in order to clear this table and be safe of the grenade that’s about to go off.

So this is really my major point here: theme is incredibly useful, and incredibly important. But it must be subservient to the gameplay.

Response: Who says that it must be subservient to the gameplay? Why? It’s true that I, Keith Burgun, tend to like games that do that, but what about a person who likes prefers games which don’t follow that rule? Maybe they’re just “wrong” to like what they like in some way, but… at least provide some explanation for why! You can’t just assert it.

Starting With A Theme?

The question of whether to “start with a theme” in a design process or not is interesting. Some people have argued whether or not it’s OK to start with a theme or not, but I actually think this conversation has it wrong. With a possible exception of the simplest sorts of games, it’s usually impossible to design with no theme in mind. Just as the theme helps a game-player understand the system he’s working with, a game designer often needs theme as a scaffolding for his design.

However, it’s important that you, as a creative architect, not let the scaffolding dominate your work. Do not get committed to a theme early on; build a lightweight, flexible scaffolding (a broad theme) and be prepared to change it when better mechanical ideas come along. Your theme should be iterative and change as the gameplay requires it to.

Response: Okay, so I actually responded to a lot more of this stuff, but then due to some awful WordPress error, lost a bunch of it.

The big takeaways here are:

- I utterly failed to recognize the fact that gameplay, narrative, aesthetics, etc, can not be fully pulled apart from one another and looked at individually. It’s kind of impossible to play a game that is totally devoid of any narrative charge. This issue is complicated, but it’s also what I would now call an irresponsible formalism in that it is looking too close for too long, and not taking a step back and looking at the world and the people in the world and what they’re doing. People are clearly playing the kinds of games that my theory suggests they shouldn’t be, so… what’s going on there?

- It’s not only sort of ignorant of what’s happening in the world, but it is also kind of gate-keepy and colonial in the ways that it tries to enforce my own aesthetic preferences on other people. When I say that “games are about their gameplay”, am I saying that some interactive product that isn’t about its gameplay isn’t a game? Or that it’s just a bad game? In either case, I am doing work to elevate myself and my games in an upper class and relegating others to a lower class.

There’s a distinct possibility that this project has been kind of incestuous and a waste of time, but as I said up front, I think it’s important. Let me know what you think.

If you liked this article, please support me on Patreon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.