Let’s start from scratch. You’re a game designer. How can my work help you?

If you’re the kind of designer who wants to tell a good story, create a lush immersive atmosphere, express a social value, or just embrace the latest in graphics technology… this article – and most of my game design-specific work – isn’t for you.

But there’s a ton of designers out there who want to make a little “fun machine” – an interactive system where the player is doing stuff, gaining mastery, and being otherwise entertained for reasons other than atmosphere, story, social values or those sorts of things.

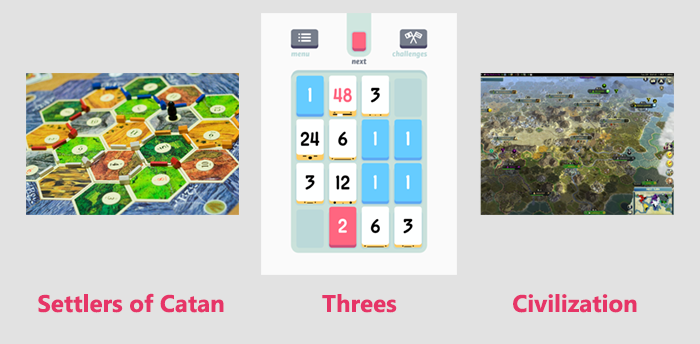

There’s a ton of game designers out there who want to make an interactive system that is engaging and interesting by the merit of its interactivity itself. Here’s a few examples.

These are just some examples of systems which are primarily played for their interactive qualities – how their rules are arranged creates an interactive environment that’s interesting and entertaining for people.

Some other examples would be Tetris, most designer boardgames (Puerto Rico, Bohnanza), most competitive videogames (Starcraft, Street Fighter), most sports (American football, baseball), ancient abstracts (Chess, Go), and most card games (i.e. Poker, Go Fish). Actually, most of the things that we would call games tend to fall in this category.

Some of these systems – particularly the most abstract ones, like some card games, Tetris, or Chess – you could say are played almost entirely for the sake of the quality of their interactions. It’s safe to say that most people are drawn to Chess because of the strategy, the tactics, the planning, etc. Of course, even in the case of Chess, there are those who are drawn to it for external reasons – feeling superior over another person, enjoying competition, or, maybe they just like how the little pieces feel in their hands.

But what I think it should be easy to agree to is that interactive systems can have interactive merit.

Let’s take a quick counter-example: Final Fantasy.

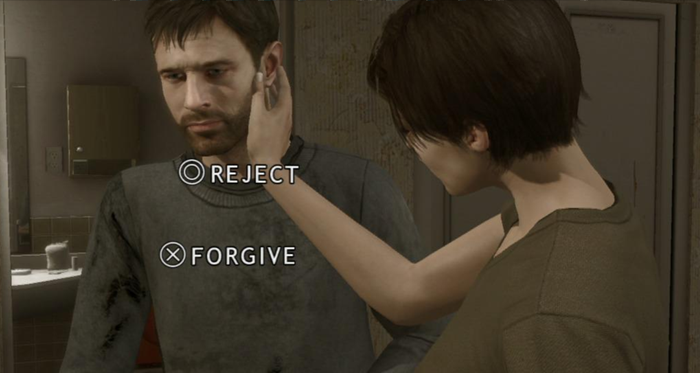

It’s pretty safe to say that Final Fantasy has less interactive merit than, say, Threes or Civilization. Certainly it has less than a highly-rated designer Eurogame. Even less interactive merit would be something like Heavy Rain.

It’s pretty safe to say that Final Fantasy has less interactive merit than, say, Threes or Civilization. Certainly it has less than a highly-rated designer Eurogame. Even less interactive merit would be something like Heavy Rain.

Much of the interaction in Heavy Rain consists of binary QTE inputs and just walking around. If you were to remove the fancy graphics and story, it’s highly unlikely that many would play with this system for its interaction.

Please note that, at the moment, I’m not making an overall value judgment on any of the systems I’ve mentioned so far. I just want to make the distinction clear between “things that are designed to have interactive merit, vs. things that are designed to have other merits”.

I’m also not (at the moment) making any declarations about “purity” – plenty of existing interactive systems have all kinds of non-interactive value as well.

So You’re An Interactive Merit Designer

Let’s say that we agree: you want to make a system which people will play primarily for its interactive merit. Now what?

Let’s say that we agree: you want to make a system which people will play primarily for its interactive merit. Now what?

What almost everyone does, especially in digital games, is start with a genre. We’ll make a first-person shooter. Or we’ll make a Tower Defense game. This approach is the easiest, and the worst, both for the same reason. The problem with starting with genre is that genre tends to be an entire game design ready to go. That makes for fantastic scaffolding, but it also is highly restrictive and explains why so many videogames kind of end up feeling like the same thing over and over again.

Maybe you’re OK with that! If so, that’s perfectly fine. But I think a lot of people feel the way I do – that we want to know what new kinds of interaction are possible. Do videogames always have to be about jumping, shooting, walking, and collecting? Or are there entirely new whole genres just waiting to be invented? I think there are, and if you’ve gotten this far, I’m assuming at least part of you feels the same way.

What Do We Do Without Genre?

Let’s discard genre and start looking at some of the possible interactive-merit-y ways that things can work, in a bigger way.

I think most people get the idea of a “sandbox” – something like Minecraft or Dwarf Fortress or Garry’s Mod. Something you can kinda “play with” – it doesn’t have goals, and you just kinda mess with it, maybe make some stuff, and that’s pretty cool.

But I think most of us feel that having some kind of “goal”, something to work towards, is kind of important for long-term engagement with these kinds of things. What am I trying to do? Yeah, I can just mess around with it, but can I do something more than just mess around?

I suppose I could create my own goal. Maybe in Garry’s Mod, I’ll make the goal of “making a hovercraft”. That’s fine, and that works decently well as a goal.

The problem is that it’s hard to come up with a goal on the fly that isn’t too hard or too easy. It’s also pretty tempting to change goals on the fly, while I’m playing, which makes it all kind of feel like “what am I even doing?” Also, once I reach my set goal, then I have to come up with another goal.

So this kind of “toy” play works OK, but there’s gotta be something better, right? Can’t we as designers choose a really great goal for players that will guide their play in a good way and alleviate them of the responsibility of having to create their own obstacles?

Prescribing a Goal

Alright, so let’s say we have a sandbox application, kinda like Garry’s Mod or Minecraft, and we want to add a prescribed goal – a goal that the rules say the player is supposed to pursue, and that the game enforces.

How about our goal is to build a tower that’s… 200 feet tall. That’s tall enough so that it should be a challenge, but not so tall that we shouldn’t be able to do it with some effort.

This is great, because now we can organize our other game rules around reaching this goal. Maybe you have to dig up dirt to get clay, and you can convert clay to bricks to create walls. Also some limitations, like your shovels break and you have to find new ones, and maybe walls crack if you put too much weight on a single one, etc.

All of these values can be tuned around that 200 ft goal, and that’s the really great thing about goals. Without a prescribed goal – if we just allow the player to come up with goals – we, the designer, have no idea “how durable a shovel should be” to make it balanced for the player’s house-rule goal.

The player plays our game, and they’re enjoying it – making decisions, building a little bit of mastery, and yeah! I think we’re pretty much established interactive merit! Hooray!

But then, something terrible happens. The player reached the goal. Now what? Well, they could play it again, but assuming things are the same, they can just do exactly what they did last time and reach the goal again. That’s far less interesting than doing it the first time. Is that the best we can do – a system whose value drops off dramatically after just one play? Civilization can be played thousands of times! Even Klondike Solitaire, which came with Windows 3.1 can be played over and over again without getting boring.

How Do We Get “Replay Value”

There’s a class of interactive systems called puzzles which don’t need to have replay value. Puzzles actually embrace their “one-shot” setup and are designed to be as interesting as possible in one play.

There’s a class of interactive systems called puzzles which don’t need to have replay value. Puzzles actually embrace their “one-shot” setup and are designed to be as interesting as possible in one play.

Similar to “designing by genre”, I think that actually people “get” puzzle design, though. Having your interactive entertainment be a puzzle is a safe route to making something that will have an audience and generally be regarded as “solid”. But first, I think puzzle design is pretty well understood precisely because it’s really just trying for less. It’s massively more difficult to design a “play-forever” machine than it is to design a “play-once” machine. I think it’s therefore reasonable to also believe that there’s a similar difference in value – or “interactive merit”.

This is not even really a knock against puzzles – it’s just that things with truly high “replay value” are just so incredibly high in value. I mean, I’ve been playing League of Legends for a little over two years, about 1-2 games per day on average (and I’m certainly NOT playing that for its “story value“, I can tell you that much for sure). So that’s a massive amount of interactive merit!

By the way: systems that are really high in replay value often are referred to as having “depth“. It’s kind of a synonym for “high replay value” or “high interactive merit”.

So how do we get this elusive replay value? There are actually a lot of ways to do it. As is a theme in this article, the understood ways are the easy ways, and the easy ways have problems. Here’s a few well-known methods for creating replay value:

- Hard Puzzle – This is actually the most common one and it describes most single player videogames. The old Castlevanias, Half-Life, and even the beloved Super Mario Bros. all qualify here. Problem: it’s still a puzzle. It might have a bit more “replay value” because it’s hard, but you still have the “only fun once” issue – after that, players start treating it as a toy and prescribing their own goals.

- “Skinner Box” – You can create a system that exploits bugs in our mammalian software by offering rewards on a random schedule. Examples would be loot drops in Diablo or gambling systems like slots. Problem: it’s not actually fun, it’s just compelling you to keep playing the same way that a gambler can’t stop pulling the lever.

- Uhhh… well, forget the goal, then! – You can also revert back to being a toy. Actually, a lot of single-player “interactive merit” systems do exactly this. Systems like Tetris and Threes offer a “high score system” which is often confused for a goal, but is really just a mechanism that the player can use to prescribe his own goals. Either way, we’re back to square one at a toy if we use this method. Problem: we already described the problems with toys above.

- Super-Random – It’s actually pretty easy to design multiplayer strategy games and have them seem to “work” if everything is just… extremely random. The reason for this is that people have a pretty hard time knowing the difference between “oh cool, my strategy paid off”, and “a random event” (related). Randomness typically comes in the form of dice rolls or card draws, but also can come in the form of massive complexity (Magic: The Gathering) or high execution (Starcraft). Quick note: randomness is an important part of a good game, but not all randomness is equal! Problem: Kind of related to the Skinner Box issue, but you’re just not getting what you think you’re getting. Super-random games are mostly based on deception.

So far, we’ve discussed two “forms” of interactivity: the “toy” (no goal) and the “puzzle” (a one-shot goal; you could call it a solution). But there’s one more easy way to create replay value that I haven’t yet mentioned, and that’s the contest.

The Contest

In a contest, you take some hard task, preferably one without a “ceiling” (i.e. one that you can kind of get better at indefinitely, not like a binary “solution” type of goal), and then you have two or more players do that task, and compare their results. Another way to look at it is that you have players doing an activity for some fixed amount of time or turns and then measure what they were able to do.

Classic contests: the pie-eating contest. The weight-lifting contest. The 30 yard dash.

How about Chess – is that a contest? Well… technically – you are “measuring” who’s better at Chess in a Chess match – although for some reason, we don’t usually refer to Chess or other “strategy games” as contests. There’s a reason for that, and we’ll get back to why in a bit.

I think most of us understand that contests are great for figuring out who is the best at something. They can also be entertaining to watch and for some people, engaging in them can be pretty fun. However, I think that pure contests aren’t really something that most people want to get super into. I mean, how many friends do you have that are “into” a contest?

What is it exactly about contests that’s kind of limiting their value? And why don’t we usually call Chess a contest?

Decision-Making

The answer is “decision-making”. That’s the thing which contests generally don’t have, and it’s the thing which really kind of defines “strategy games” like Chess against something like a contest.

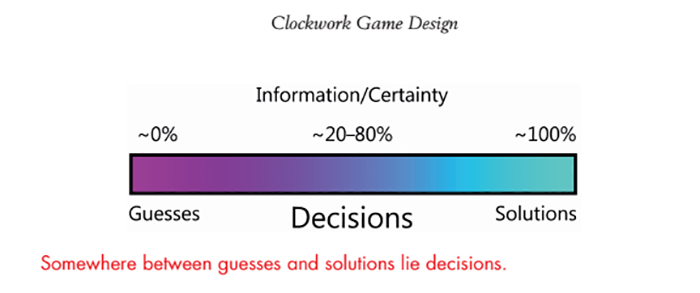

Decision-making is actually a pretty special thing – it only happens when a person understands the system enough to do something better than just make a blind guess, but also doesn’t understand it so well that they basically just have the solution. Here’s a little graphic I pulled from my book, Clockwork Game Design:

So far I’ve talked about toys, puzzles and contests. Now, we’re talking about the fourth and final interactive form, which I call “the game”, which is a contest of decision-making. Keep in mind this is a prescriptive definition – I know that the word “game” gets used for all kinds of things in normal every day speech. If it bothers you, or for clarity, I recommend using the expression “Clockwork Game” to refer to this prescriptive form.

So far I’ve talked about toys, puzzles and contests. Now, we’re talking about the fourth and final interactive form, which I call “the game”, which is a contest of decision-making. Keep in mind this is a prescriptive definition – I know that the word “game” gets used for all kinds of things in normal every day speech. If it bothers you, or for clarity, I recommend using the expression “Clockwork Game” to refer to this prescriptive form.

The problem is that human beings are really, really smart, and yet, they have limits. So you can’t just give them insanely hard decisions – picture checkers with a 100×100 grid or something – but if you give them something reasonable, most of the time they’ll just solve it pretty quick.

Keep in mind that we’re not doing all of those classic videogame things. Our system isn’t a super random skinner box thing. It’s also not a toy – it has a goal (so no “high score” model – if it’s score based, there needs to be a binary win/loss condition!). It’s not a puzzle, because even though technically every game with a goal does have a solution, puzzles are designed to get solved, and games are designed not to get solved.

A Clockwork Game is not just like any other videogame or strategy game. It is a single, elegant system, built around a core mechanism, with nothing but the necessary supporting mechanisms and a carefully chosen goal. Through the careful use of this design pattern, we can achieve elegant, super-deep, novel, and super-fun interactive systems.

Designing Clockwork Games

What I’ve just walked you through is actually the super-quick version of the journey I’ve taken as a game design theorist over the past decade. Over the years I’ve been honing in on some essential thing about interactive systems and trying to figure out how to bring it out in the most effective way possible.

I believe that the Clockwork Game form is not only the best, but as far as I can reason, the only way to produce high-depth, elegant, efficient interactive-merit-based systems. Clockwork Games have the potential to not just match, but be vastly better than the systems we’re used to.

So how do you go about designing clockwork games? This article has already achieved its goal if you agree to the project of designing clockwork games.

Well… that’s what I write about at this site! AFor a quick starter, I’d check out my 3 Minute Game Design video series. If you like that, consider purchasing my book, Clockwork Game Design. Also, don’t forget about the countless articles on this very site, or my podcast, the Clockwork Game Design Podcast.

Also: designer European board games were a big inspiration to me; I think they are knocking on the door of coming to the same conclusions I have, so I’d recommend checking as many of those out as possible if you haven’t already.

Thanks for reading, and please let me know if I’ve convinced you or not in the comments!

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider supporting my work by becoming a patron at Patreon.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.