Today I wanted to talk a little bit about the game design of Dragon Bridge. Dragon Bridge is a two player competitive card game. I originally designed it very quickly—in a matter of a few hours—as part of the #18CardStrategyJam, and I had never had the experience before of making a game that kinda “worked” so quickly. Part of this was because of the limitations, but another big part of it was that I had actually tried to design this game about 30 separate times in the past, between the years of 2010 and 2015. None of those prototypes did what I was hoping they would do, but they all taught me something about what might work or not work in a two-player “track” style grid battle game.

I had been inspired, originally, by games like Reiner Knizia’s En Garde (as well as David Sirlin’s asymmetric-powers version of the game, Flash Duel), and I really wanted to make my own game along those lines, but I had a lot of problems making such a thing work. I guess maybe my subconscious had been chewing at it for the past four years, and/or maybe I’ve gotten better at game design or something, because when I sat down to try again, it sort of came together easily(relatively speaking).

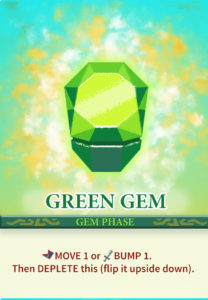

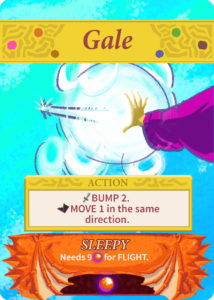

To give you a basic sense of how the game works, players play cards from their hand (action cards, as seen in the Dragon Stack above) to either move their character or bump the opponent. Players’ positions are indicated by the purple arrows on the character cards (the red and pink cards in the middle there). The objective is to bump the opponent into the orange area of the track close to the dragon, OR to start their turn on the orange area furthest from the dragon. Sounds simple, but the issue is that the dragon is switching sides now and then in a semi-predictable and semi-controllable way. You also have these green gems which you can use for a little extra power, or if you save up three of them, you can buy a Magic Item, which permanently powers you up. You can gain more Green Gems by stepping on those little green gem tiles on the grid. Finally, your character has a special ability that triggers under certain conditions. That’s about it!

To give you a basic sense of how the game works, players play cards from their hand (action cards, as seen in the Dragon Stack above) to either move their character or bump the opponent. Players’ positions are indicated by the purple arrows on the character cards (the red and pink cards in the middle there). The objective is to bump the opponent into the orange area of the track close to the dragon, OR to start their turn on the orange area furthest from the dragon. Sounds simple, but the issue is that the dragon is switching sides now and then in a semi-predictable and semi-controllable way. You also have these green gems which you can use for a little extra power, or if you save up three of them, you can buy a Magic Item, which permanently powers you up. You can gain more Green Gems by stepping on those little green gem tiles on the grid. Finally, your character has a special ability that triggers under certain conditions. That’s about it!

So with that out of the way: here’s a few things that I think are cool game design accomplishments of Dragon Bridge, that hopefully other designers can get something out of, or could possibly inspire others in their designs. Enjoy!

1. The “Green Gems” system

One of the fundamental problems this game could have is a feeling of staleness: I move 3 tiles forward, and then you bump me 3 tiles backward, and it’s like those two turns barely even happened. Later in the game, you’re no more “powerful” than you were in the beginning, so there’s nothing bringing things toward a conclusion.

One of the fundamental problems this game could have is a feeling of staleness: I move 3 tiles forward, and then you bump me 3 tiles backward, and it’s like those two turns barely even happened. Later in the game, you’re no more “powerful” than you were in the beginning, so there’s nothing bringing things toward a conclusion.

Toward the end of development, the amazing Brett “Brickroad” Lowey of BrainGoodGames helped me realize how much of a problem this was, and pointed me in the right direction of a solution. In response, I came up with the Green Gems system. Basically players each have three face-down green gems. When they end their turn on a Green Gem tile, they can flip one face up (there’s also a card called Soda which lets them flip one over).

Green Gems are kind of like free move/bump cards you can play on your turn, and you can play more than one of them in a turn. If you save up all three, you can flip them all to get a Magic Item, which is like a permanent buff (such as +2 to all your bumps, or “bump 2 every time you move”, stuff like that).

This system accomplishes four things really well:

- It acts as a short term tactical power meter, so I can have a little bit more power than you because I have 1 or 2 more green gems available than you do.

- It acts as a vector toward long-term investment (econ) strategy in terms of gaining those permanent magic items. Well, sort-of-strategy; this isn’t really a strategy game, it’s more tactics, but this is where it gets its longest arcs anyway.

- It acts as a vector for disruption; as another resource that can be “attacked” or manipulated. The game is so minimal that it can be hard to come up with good “disruption” moves, but now you can easily have a card that says “the opponent flips a face up Green Gem” (which we do have).

- It acts as a kind of “health” for the end game. As a player is pushed into the edge where the dragon is, they will often have to use any Green Gems they have to survive. This gives a little wiggle room for a player so that losing isn’t super abrupt, and it means that a player who is trying to push a player into the dragon has to be able to do it a few times in a row to make it count. Note: this same dynamic also happens with an escaping player getting bumped back away from the escape tiles.

Thematically it also feels right for a game in the Gem Wizards universe that you have these gems which are giving you additional power. And at three cards, it’s just enough to give you enough resolution of power without mucking up the table with too much “stuff”. I’m really happy with it!

2. The dragon orbs

The “core mechanism” of Dragon Bridge has to be moving, either moving your wizard or the opponent’s wizard. But the strategic core of the game, the supporting mechanism you have to think about just as much, is the Dragon Orbs system. Most Action Cards have some number of little orange circular orbs at the bottom of them—many cards have one, a few have two, one has three, and several have none.

Each time you play a card for its action, the dragon orbs stay there, adding up, and when there are 7 or more there, the dragon switches places. If there are ever six cards down and not enough orbs, though, the cards get reshuffled—basically, the dragon orb count starts over, leaving the dragon where it is for awhile longer (this is called a “Roost”). So there’s a lot of playing around this. Do you push further toward the edge, trusting that you’ll be able to get the dragon to fly away in the next few turns, or no?

And it gets more complicated because there are some cards that let you take a card back from the pile, an item that allows you to temporarily modify the number of orbs, and other trickery that makes it hard to ever perfectly predict. Overall it works really well as a very simple but elegant “other thing” you have to worry about that isn’t just the “pushedness” on the map, which could be (well, quite literally is) one dimensional. We also needed a way to have the dragon switch places in a way that’s somewhere between predictable and unpredictable, and now it’s kind of a “negotiation” between players that can’t ever be totally mathed out by anyone because of all the possibilities.

3. The Wizard powers (and Item powers)

I always knew I wanted each character to have their own power(s) to create variety in that asymmetric “factions” sort of way, both because it’s just a cool way to hit a system from different angles, but also because it’s a great way to build some characters and lore into the Gem Wizards universe. In early versions of the game, the Wizard power was like an active ability that you could use. But this had a lot of problems: it was hard to make this any kind of strong ability with a lot of identity, because we didn’t want you to use it instead of a card really (we need you to keep playing cards for the Dragon Orb system to work right). So they had to be these tiny incremental abilities that just felt sort of crappy.

I tried a few different things, but ultimately the best thing seemed to have them be “When You…” abilities. Basically, the Wizard powers are things that happen when you meet some other special criteria, and usually not something you can do terribly often. So Bunny Wizard‘s power is, if he passes the other player on his turn, he gets to MOVE 2. Derby Pocket‘s power is that he gets to move 3 tiles anytime there’s a dragon “Roost” (which is the thing where there are six cards down and less than seven orbs).

Magic items, the permanent upgrades you get, work in the same way. This system is nice because the basic actions of the game can just be happening, and then they’re modified—added to, changed, other effects are triggered, etc.

4. The Win/Loss conditions

One concern I had with the game was the idea that you’d just push someone back 3 tiles, into the “end tiles” section, and the game would just suddenly and anti-climatically end. Actually, this is a problem that I sort of have with En Garde—a much simpler game, but it always felt kinda like “blah” when the game ended. It felt like winning should require a little more “pushing”. So the cool thing here is, there’s a few conditions on winning:

- If the opponent is in the end zone near the dragon (the first win condition), they make the loss check at the end of their turn, so they always have that turn at least to escape with whatever resources they have (cards, Green Gems, etc)

- If you are in the end zone far from the dragon (the other win condition), you make the win check at the start of your turn, so you must have gotten there last turn and the opponent had an opportunity to bump you out.

- Finally, you can’t win or lose on a turn that the Dragon switched sides. That’s another thing that feels bad, when you’re one tile away from winning and then suddenly now you not only don’t win, but also, you lose, that quickly, especially given the ways that the game makes winning or losing difficult.

5. Tiny cycling action deck

The game has just 16 basic action cards (four of which are doubles). Each player has a hand of four cards, and up to five could be face up in the Dragon orb pile (action cards you’ve already played) before the Roost. Also, I didn’t mention this before, but when the dragon switches, it gains a new power that’s based on the last card played (the card that triggered the dragon to switch sides), so that’s another card that could be under there. That leaves at least two cards that would still be in the deck, even when so much of the deck is face-up public information.

The really cool thing about such a small deck is that it makes this one of the least random card games out there. I’m not sure that the cards are all completely balanced against each other yet. But even if they’re not, you go through this deck extremely quickly, and if you don’t have “good cards” now, in a few turns you’ll have the other half of the deck and things will have reversed. Beyond that, as I mentioned, once cards have been played, you can sometimes draw them back up to your hand.

For me, navigating the information horizon is a really big important part of game design, and it’s something that’s really hard to do in tabletop games. Too many card games have pretty bad variable randomness, where sometimes you just draw better or worse. Dragon Bridge really doesn’t have that because of the small number of unique cards and a tiny deck. You draw the same cards every game, just in a different order. What makes the game different each time, what gives each match identity is NOT the cards you draw. Instead, it’s:

- What powers the Dragon gets

- What characters are in play

- What Magic Items get drawn (this could conceivably have some degree of variable randomness to it, but we’ll keep an eye on it! It’s only 5 cards, so it should be pretty balance-able.)

As well as of course, just all the details of what happens. Just to clarify: this game would probably function without items, characters, or dragon powers. Those are just there to help each match feel different and change the valuation of the basic cards.

All in a tiny package

All of this happens in just 36 cards—not even a full poker deck! I feel like it’s really elegant in that way. It doesn’t have the depth of a huge Eurogame, but I do think it has the depth of a game that’s significantly “bigger” in terms of components and rules than it has. The rulebook right now is about three pages long, and I’ve already explained basically all of the rules here in this blog post (and that wasn’t even the goal here).

It’s been a really different process for me, working so quickly and finishing it so quickly. I intend to start a Kickstarter soon for a print run of the game—if you’re interested in hearing more about the game definitely sign up for my new mailing list. You can also play the game in Print and Play form right now, or try it out on Tabletop Simulator here.

Thanks for reading, and let me know if any of this seems cool to you! Or if you have any other thoughts or suggestions. Until next time!

You must be logged in to post a comment.